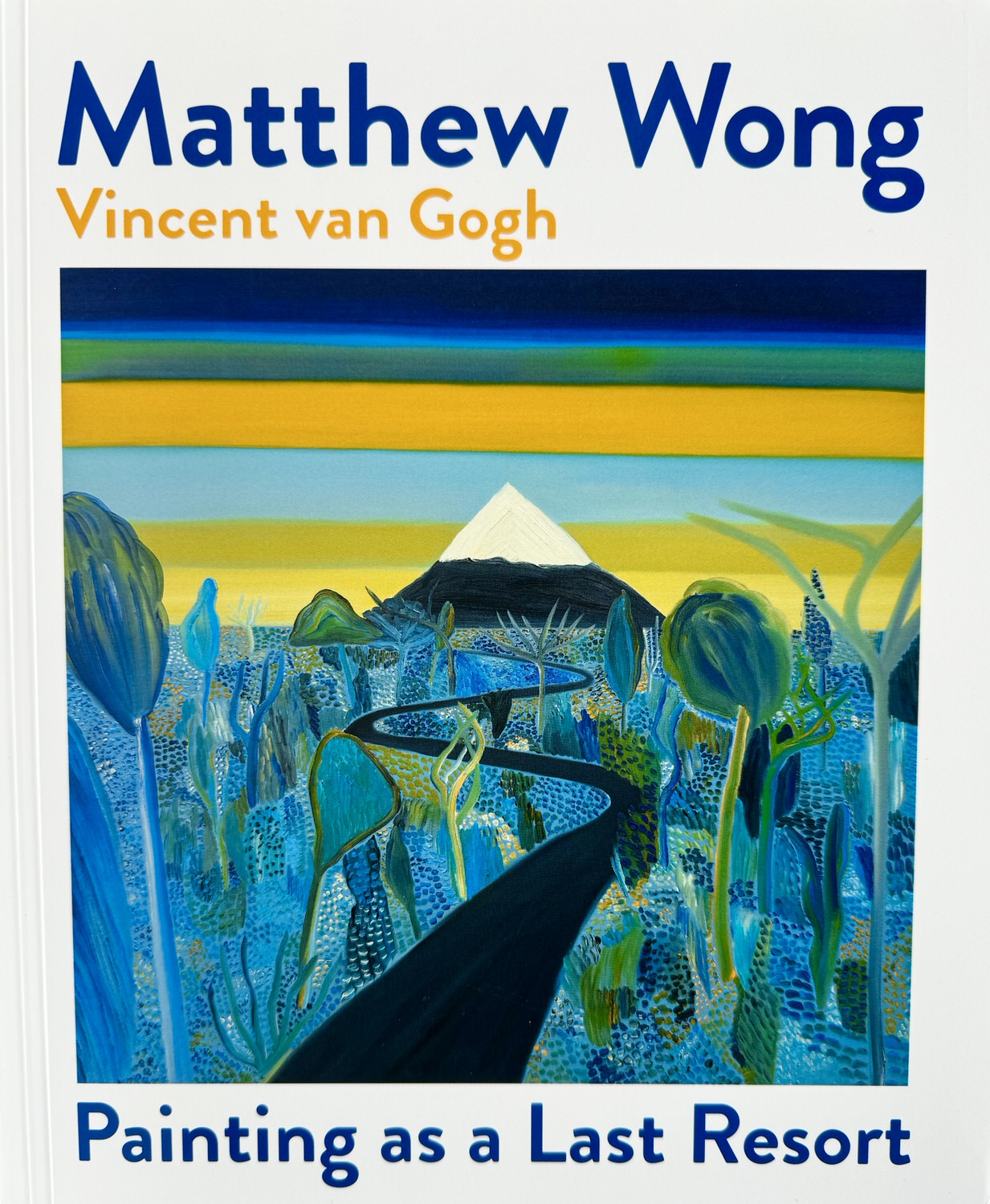

It is an honour and a privilege to introduce this catalogue on the work and life of Matthew Wong for the occasion of the joint exhibition with Vincent van Gogh at the Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam and the Kunsthaus Zürich.

Life affects people in different manners with differing degrees of ferocity. How we physically navigate our way in the world, carving individual paths through the muddle, also bears on our sensitivities and sensibilities. Pursuits take shape, some impacted by circumstances (both innate and outside our control) while others are volitionally moulded by sheer will. Matthew Wong’s art life was the reflection of an agitated, obsessive curiosity that could never be sated, leaving him exposed, yet stridently in command. For Matthew – and Van Gogh, with whom he is paired in this exhibition – the vibration of colour was felt (and expressed) like a finger poked into a stripped nerve.

Art is creative destruction that entails taking what’s been done before, historically, and putting it through a blender to re-contextualize and recast it. Artists are not acquiescent witnesses merely mirroring the world around us, though they do that too, but critics of society and technology. Van Gogh did not solely paint sensuous sunflowers and sunsets; he simultaneously signified aspects of poverty, working-class subjugation and social issues – from the plight of peasants to conditions of prisoners. Matthew’s post-mortems were introverted: confronting, prodding and mapping states of psychological actuality.

Imbued with a sense of desolation, cloaked in disaffection, you can taste the solitude in the making of Wong’s paintings; still, Matthew had a light-hearted, animated social presence. Aside from the appearances of a formal language steeped in traditional drawing and painting, social media played a key role in his process, contributing to his education, development and overall mindset. I wouldn’t say Wong was self-taught as a painter – he studied cultural anthropology and photography at university – but rather gleaned his applied skillset scraping knowledge and techniques from the people he admired and accessed via Facebook and Instagram. I was lucky enough to be one of them. Speaking to Matthew, you could grasp his restlessness and impatience, while he was also sponge-like, foraging for information he could suck up and harness for his own undertakings.

Matthew would go in and out of periods actively engaging with his network of contacts online, then withdrawing like a turtle in its shell. He would contact me and express concern as to whether his profile should be forward facing or inward, whether to expand or contract from the participatory nature of what is nothing less than a contact sport. Towards the end of his life, he fixated on posting disparate pairings of artists, comparing and contrasting their works like a DJ spinning staccato song fragments. Often the connections would be indecipherable, other than to Matthew himself. Conversely, they were fascinating and elucidating, providing insight into the way his mind functioned like an atom smasher, and would have made for a riveting book.

Paintings, such as Landscape with Mother and Child (2017) and A Walk Through Primordial Garden and Dialogue (both 2018) are fervidly redolent of lust and passion. You all but expect to hear an accompanying soundtrack blaring in their wake. The works are cinematically epic like mini narratives or short stories, but don’t expect closure by way of a happy ending; simultaneously, you are left with incongruous sensations of elation and hope while feeling alone and lonely. In Coming of Age Landscape, Somewhere and Good Morning, all dating from 2018, the palettes are pared down to no more than a handful of colours while managing to convey the spectrum of a rainbow. Wong was adept at manipulating paint and emotion with equal acuity.

While Van Gogh and Wong regularly couched their paintings in the genre of landscape, these are anything but prosaic backdrops for mere topographies. What you see are twitchy, voluminal swirls of treacly swathes of pigment, as sculptural as they are painterly. They are invitations to climb physically into the compositions and get lost – once adrift, perhaps we’d experience something akin to the stoic impassiveness seemingly felt by both artists. Remote characters trapped in grim circumstances, as featured in the writings of Samuel Beckett, come to mind rather than the works of other visual artists. You could try and search for narratives, but Wong’s meanings are largely hermetic and unknowable – they pull you in while purposely keeping you at arm’s length as well.

Matthew was cool in his appearance – his personal style expressed via emerging designers held deep interest – and calm in his seeming level-headedness. He couldn’t be swayed by trends in art or fashion. There was never the impression of any internal torment or unrest other than as represented in the works. Like Matthew, my 21-year-old son Kai, a personable, talented artist in his own right (we all spent considerable time together), also took his life, never for an instant betraying his inner distresses or despondencies. To be with either was uplifting and fun in that they were effortlessly communicative all the while giving and inspiring. There were no clues as to their sufferings, which were clearly unendurable.

Matthew teased us with his tragically foreshortened life and works, advanced beyond the years of formation, leaving us discontented, wanting more. That so much, of such profundity, could have been painted so swiftly is mind-boggling. His beguiling, playful spirit, voracious in its capacity to absorb everything within (and without) his grasp, was also supportive and generous, considerate of others. It is futile to speculate on what might have been – undoubtedly staggering and magnificent. We are better served absorbing and contemplating what is before us: a fully-fledged body of work, adding to the canon something old and new, analogue and digital, steeped in history and ahistorical. Art is a means of self-expression and communication; with this writing and exhibition, Matthew Wong continues to do both